On Wednesday 31 January, British Expertise was delighted to host Kate Lonsdale, Director at Climate Sense, as keynote speaker at our Climate Change Networking Evening.

For the last 27 years, Kate has worked on adaptation to the climate change, supporting civil society, academia and policymakers, and within organisations that aim to create a bridge between these different sectors. Most recently, between 2019 and 2023, Kate co-championed the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) funded, UK Climate Resilience Programme and she has been a Director at Climate Sense since 2021. For part of this time Kate is currently seconded to DEFRA to support the development of a monitoring, evaluation and learning framework for the Third National Adaptation Programme (2023 – 2025).

For this conversation, we were joined by participants representing a diverse range of member organisations who provide climate adaptation and resilience services internationally. As usual, in the room we had a plethora of sectors – transport, energy, innovation, policy, advocacy and finance, to name just a few – from innovative SMEs to larger companies.

Kate spoke about the nature of the adaptation challenge. She described it as an intractable or ‘wicked’ issue due to its complexity, with no clear end point or simple solutions. Despite this, she remains passionate rather than jaded. Tackling such issues requires working across organisations, sectors and people to try to understand the whole system. Approaches need to be flexible, iterative, comprehensive and tailored to each individual case. Unfortunately, the way organisations work, and the design of incentives in the wider systems, mean that we are often ill-equipped to tackle wicked issues appropriately, at the right scale, and in a timely manner. This has consequences which are likely to increase costs. These consequences will not play out equitably or fairly across society.

In describing the skills needed to coordinate such multi-sector change, Kate used the Dutch metaphor of “a wheelbarrow full of frogs”. The task, though theoretically possible, is difficult to achieve in practice due to having to balance multiple moving parts (or multiple stakeholder perspectives) while maneuvering across potentially difficult terrain.

Early in her career Kate was involved in the establishment of the UK Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP) in 1997. UKCIP was set up to be to operate as a boundary organisation to facilitate learning and collaboration between policymakers, organisations wanting ways to adapt, and expertise in climate science and the climate projections. Even from these early days it was apparent that the provision of information about the future climate was not enough to create change.

Kate reflected on her stance as an adaptation practitioner building also on experience in community consultation, a practitioner community of practice and a master’s on organisational change. Key learning included:

There's often a disconnect between what we profess to aspire to ("espoused theory") and how we actually behave ("theory in practice") in organisations or as individuals, as noted by Agyris and Schön (1974)[1]. Frequently, our actions contradict our stated values, and, worryingly, we are not always aware of this. Organisational practices compound this misalignment by prioritising action and hitting targets and discouraging open reflection on challenges or mistakes. This failure to incentivise honest self-assessment hinders the learning needed for continual improvement of adaptation practice.

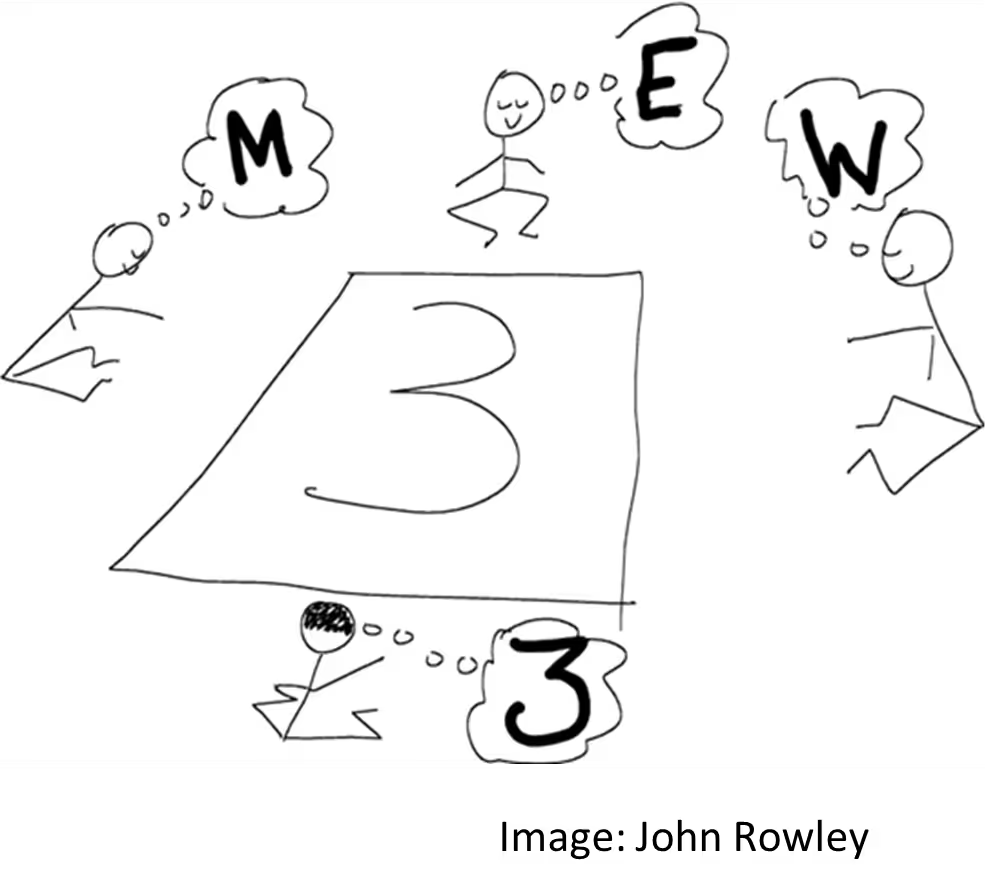

Kate used this image to illustrate that different people look at the same adaptation situation and see different things. In the image the people are only thinking about what they are seeing. Their knowledge remains ‘tacit’ and in their own heads. We need opportunities to share our thoughts, even the tentative ones and make them explicit. Too many projects plough on assuming that we are all seeing the same thing. We need to learn to see situations through the eyes of the others who will be affected and not impose our own understanding.

Kate shared another image from Sam Kaner’s Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision Making (2007). In making good adaptation decisions it is necessary to gather ideas and perspectives from diverse groups to deepen your understanding of the change needed. This is not easy and will take time. People who want action quickly find ‘sitting with’ the situation hard. But in rushing straight to action some perspectives get drowned out. The “groan zone” in the image illustrated this challenging but necessary part of the journey and can be an opportunity to address power dynamics that constrain the possibility of holistic decision-making.

Kate then shared the ‘5A’s’[2] model that she found helpful in making sense of how we adapt to climate change:

- Awareness: access to trustworthy information about what is happening (the climate science and other aspects of the situation that affect decision making)

- Agency: knowing what to do, having responsible people, understanding how climate risks affect the priorities of the organisation

- Association: having opportunities to learn from others, share experiences, have a common platform to advocate for change

- Action – learning cycles: did we do what we planned? Does it get us nearer to our goal? Are we getting better at questioning our assumptions about how change happens?

- Architecture: the container that exists around the specific adaptation situation i.e. the organisational culture, politics, legislation, media, standards, codes, regulations, technological know-how.

Each ‘A’ is not sufficient in isolation, meaning that any change programme must work across all five. Each “A” is a necessary piece of the puzzle and there are multiple linkages between them.

Finally, Kate explained that she had been attracted to work at Climate Sense because they have the approaches, ethos and tools that fit with her understanding of what is needed to support change i.e.

- learning (and change) happens through conversations;

- good conversations ‘don’t ‘just happen’ they need to be designed for and need skilled facilitation;

- it is useful to get ‘the whole system’ in the room to understand interdependencies that may not otherwise be obvious;

- when making decisions we need to understand the thresholds where we shift onto a different track if we are to avoid locking into dead end (‘maladaptive’) pathways.

Kate introduced Climate Sense’s CaDD tool which gives organisations a language and a guide to navigate the complex internal and external challenges that can impact their ability to adapt to long term climate risks. You can read more about this tool in detail here. She also spoke about the rapid adaptive pathways approaches (RAPAs) for decision making that build on her Climate Sense colleague’s Tim Reeder’s work as project Manager of Thames Estuary 2100 and the work of Climate Sense in leading the development of the ISO Standard on Adaptation to Climate Change. More on this can be found here.

[1] Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A.(1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

[2] Ballard D and Black D pers comm.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)